Hybrid Reflections - Mediating Grounds in Chittagong

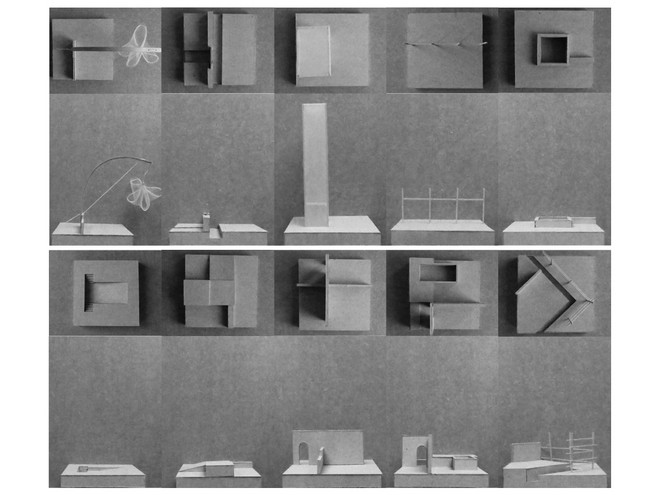

Initially, the project studies dualities and paired terms, problematizing how this type of ordering forms how we conceive and look at the world.

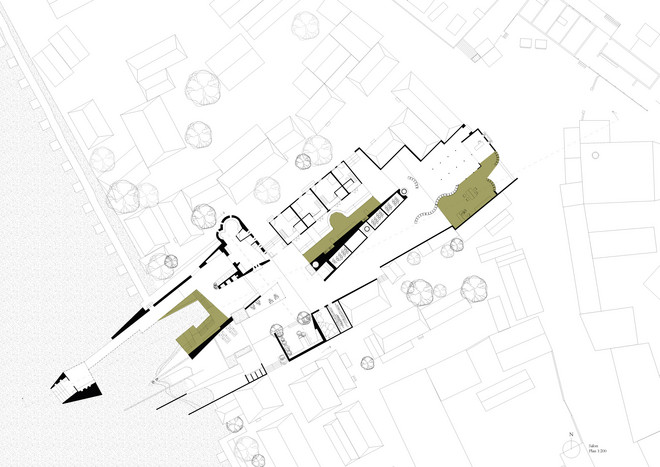

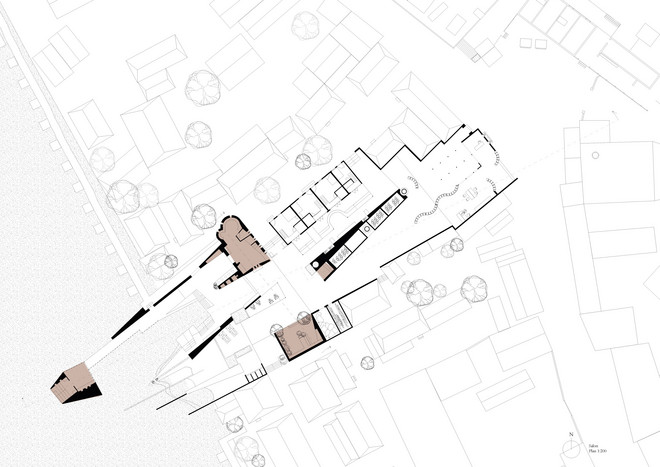

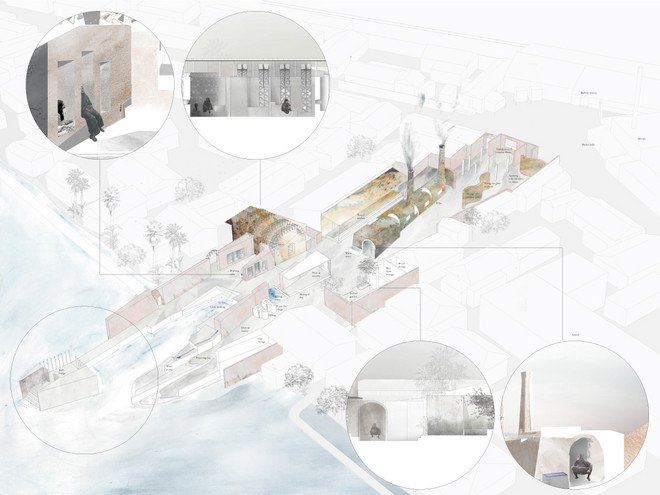

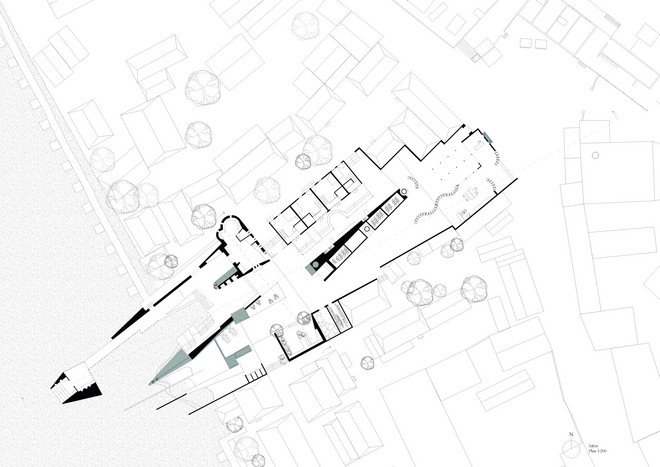

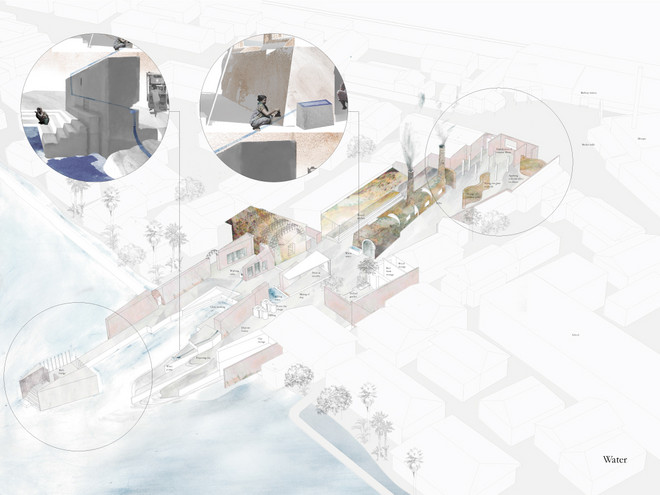

Two concepts - that of the salon and the garden – are being recognized as liminal and in-between spaces, mediating between constructed dualities. They are used as programmatic frames for two sites in Chittagong, Bangladesh; forming ground for two interventions.

A small-scale production of ceramic water filter and a seed library.

The work is focused on the relation between the two sites, the field they are creating. Connections are made, down to the scale of a burnt clay element, which is related to the soil and the water.

The project concerns the everyday life of the people involved, residing in practices of washing, cleaning, sowing, cultivating; giving dimension, understanding and marvel to these routines and customs.

links to programs on issuu:

http://issuu.com/beata9/docs/program_beata_hemer_stud5550/1

http://issuu.com/beata9/docs/booklet_printa_t_utst__llnig/1

--------------

The project is based on a three weeks long study trip to Chittagong, Bangladesh made in November 2014.

Chittagong is the second largest city of Bangladesh, a major port city and is a hub of economy and business. It is located on hilly terrain, on the banks of the river Karnaphuli, and is in the west facing the Bay of Bengal.

It is a monsoon city, with a rain season lasting from May to August, which highly affects the daily life of its inhabitants. Methods to handle this abundance of rain are also visible in the cityscape.

It was through following the water I started to move towards the outskirts of the urban fabric, towards the seashore and the lowland.

Starting at the hilly urban areas, by a big pond, I moved towards the west.

To walk the way, mapping the road with my body and feet came to be an important tool for understanding the landscape I moved through.

Through the walk I registered phenomena connected to water, such as dried-out rivers and polluted ponds. The walk thus became a map, a landscape relating to water, on a scale between urban and rural, highland and lowland.

I saw the mapped landscape of water bodies as a point of departure for studying dualities and paired terms, how they form and influence our thinking and conception of the world around us.

Urban-rural, nature-culture, private-public, indoor-outdoor are all examples of paired terms that too easily becomes congealed, and that often are used when describing places and architectures.

In my work I have recognized two concepts as liminal and laying in a field between constructed dualities.

It is that of the salon and of the garden.

Both the salon and the garden are loaded with heavy connotations; of French aristocracy, English gardens, bourgeois meetings, feminist utopias.

The concepts emerge somehow from a similar wealthy western world, seemingly far away from the everyday reality of Bangladesh.

Here, I use them as initial "frame programs", which serves as a method of approaching the context, where they put an extra layer of imagination into my experiences of the sites.

The discourse of the salon and that of the garden, both mutates in the context of Chittagong. Their inherited associations are confronted with a reality that opens up the concepts, and serve as a method of working.

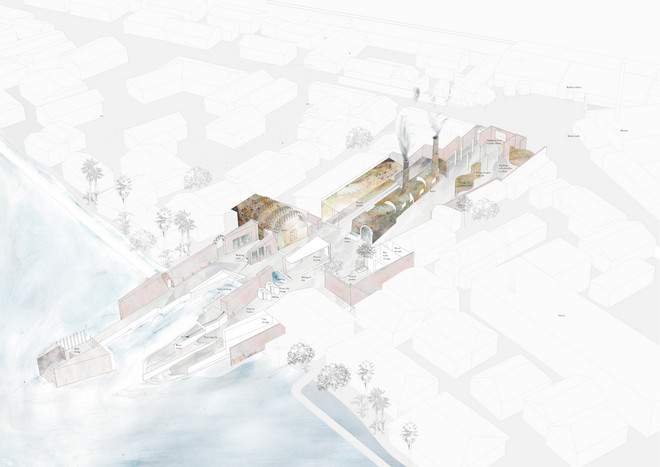

THE SALON

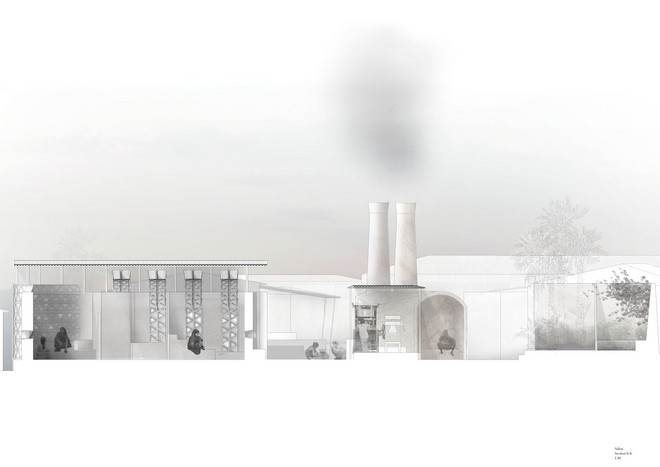

The place of the salon is an area at the eastern shore of the pond Behlvar Digi, which lays approximately four kilometres inland.

Between the market place, and the shoreline of the pond, houses lay tightly packed, with narrow alleys and greenery between. The typology of the houses has a temporary and light character, where metal sheets and woven jute and bamboo are dominating as building materials. The daily life is taking place outside the enclosed dwellings, as well as within the houses. And much of the space in-between is shared among the households. The back of this neighbourhood faces the pond, with “ghats” or steps down to the water. The uses of the pond are somewhat gendered, where the women are doing dishes, washing clothes and being busy with domestic chores- activities connected to the home. The men and boys are playing, swimming, fishing and washing themselves before prayer, using the pond as a public space.

The salon is taking place in this context, on the eastern shore of the pond, between the station and the water. Nesting in-between the existing houses, it is further emphasizing this already blurred line between private and public, outside and inside.

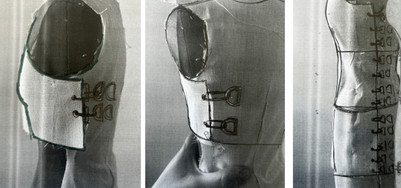

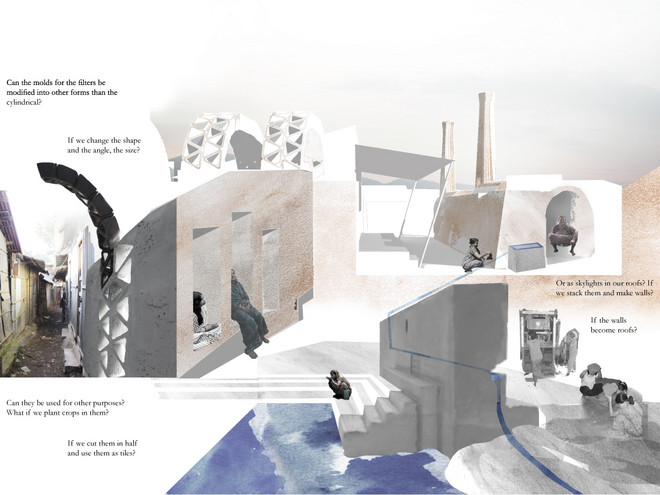

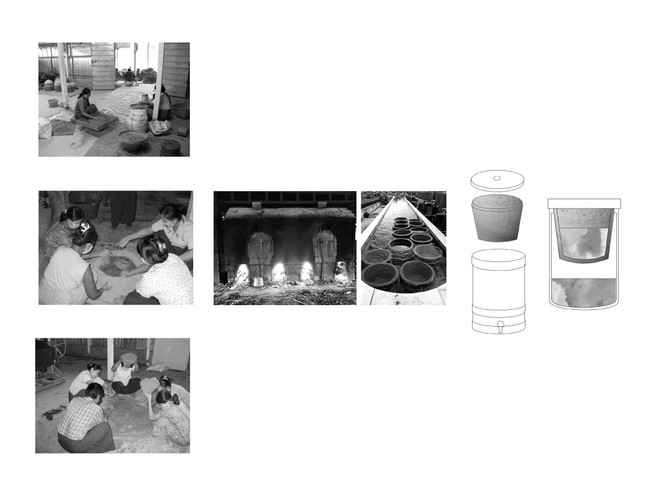

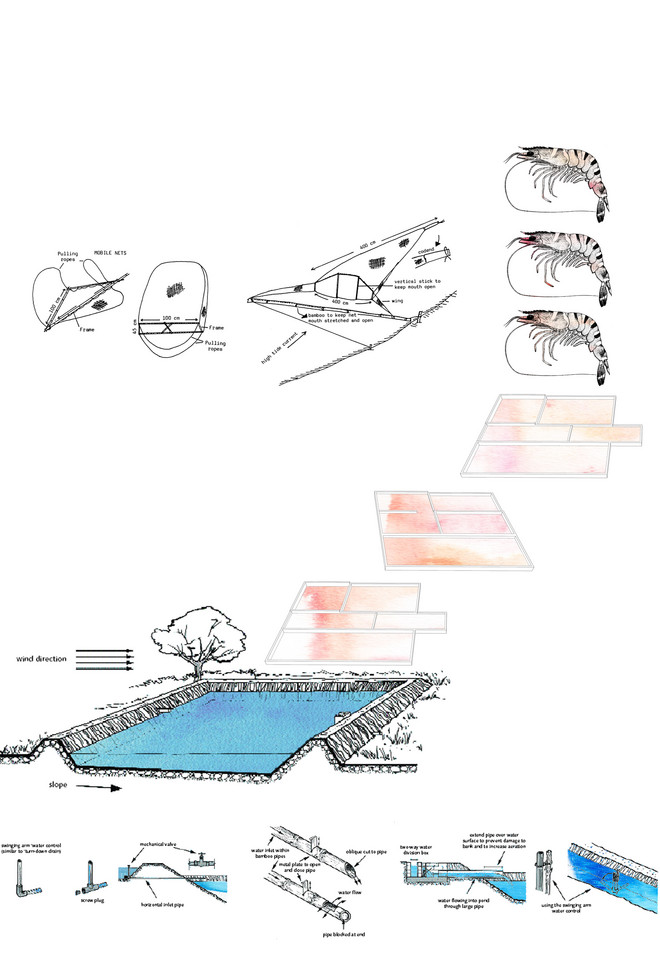

Within the frames of the salon a more function oriented program is applied. It is that of a production of ceramic elements. Through the production of these ceramic water filters, the uses and manipulations of water are further amplified. Both through the manufacturing of clay, which contains a certain procedure involving water, but also in the end product, which is a ceramic filter used for making potable water. The technique is a recognized and well-implemented low-tech method to filter water, through a porous ceramic pot.

The overlapping between the domestic space and the production of the ceramic filters is the core of the salon. The artefacts and spaces of the production lie nested in the salon, where domestic chores and everyday-life are present. The production becomes a communal act, but within the realm of the so-called domestic sphere, and therefore also accessible and changeable for the people living there.

The salon as a room for exchange and development of ideas is meant to be an initiator for a change of the filter production, where the mono-use of the filters are questioned and modified accordingly.

The salon is tightly connected to the idea of an event, where the rhythm and repetition of actions are contributing to the impressions of the space. The everyday routines repeat themselves, and set the daily tempo of the salon. Parallel, the firing of the kiln follows another tempo. The firing might take place once every second week, during a couple of days. It’s an event that highly affects the area, and is an opportunity for a festive occasion.

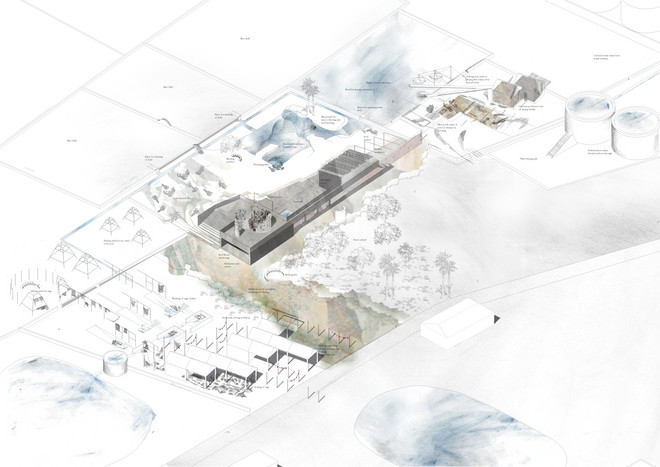

THE GARDEN

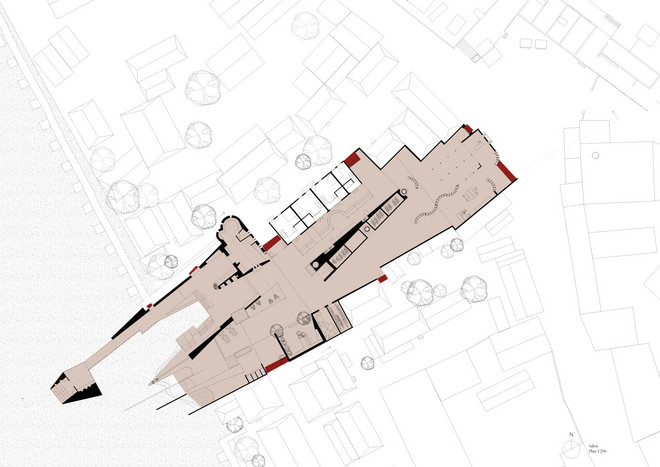

The second site is located close to the seashore, in the rice paddies.

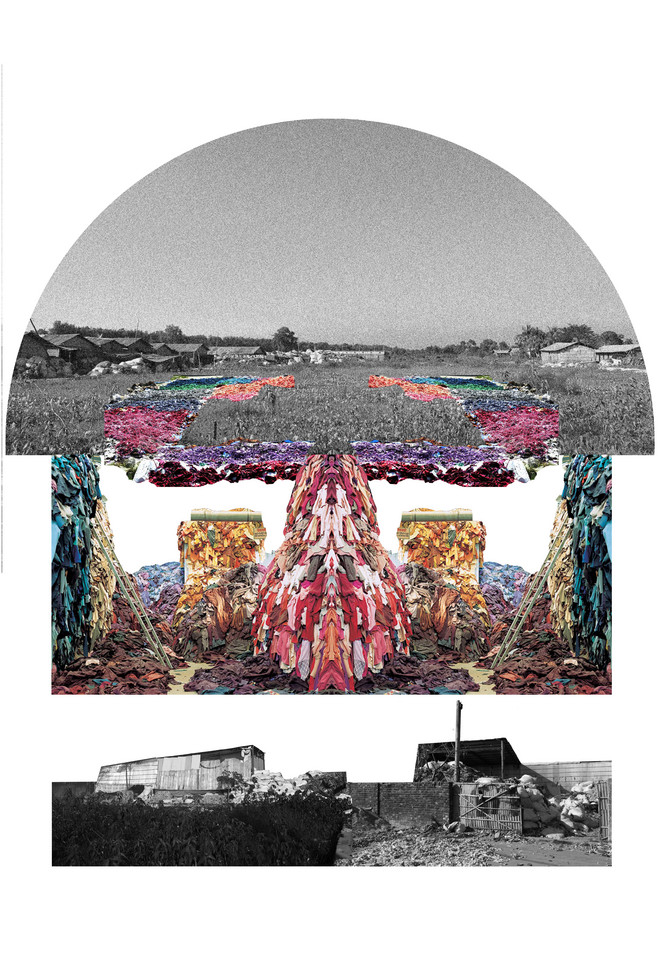

The landscape is characterized by the horizon and the openness, and by the different forms of production that take place here.Passing by, on the road, the recycling of garments is what caught the eye, and what carries the strangest beauty. More than the recycling of rags, there are rice cultivation, shrimp farming and textile washing industry in close proximity.

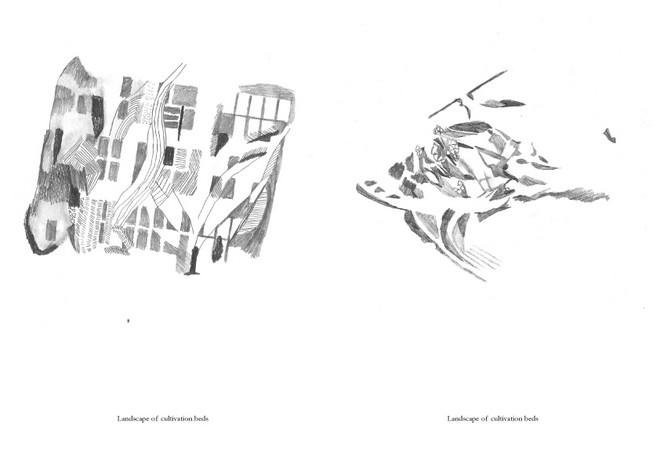

A way to approach this landscape was by identifying and mapping the different forms of industries, and to link them together both through their leftover-products, and by imagining architectural artefacts or spaces that that could be shared among them. Racks for drying clothes can be used for drying rice, ponds for shrimps can be used for rice cultivation, beds for drying and sorting clothes can become stages and landmarks. And so on.

The production cycles are linked and further condensed, moving closer to each other, forming a parkof production.

The park is creating an awareness of the existing uses of the landscape, deriving from the idea of the landscape memorial.

A memorial is a structure erected to remind people of a person or past event. This memorial, in the rice fields outside Chittagong, is reminding people of an event that is on-going, for the surrounding current now. Just as the memory is a way of paying attention, of being aware, the memorial invites one to be aware of the landscape, of the shifts and changes, cycles and events.

By being conscious and taking care of the landscape and the soil, engaging with it, the idea of the memorial turns into a garden. A garden where knowledge is shared, and the ethics of care can grow.

The garden is a test bed for future crops, an enclave of soil and plants where conditions can be controlled and modified, giving opportunities for testing of new (and old) farming methods.

The central part of the garden is the seed library, where farmers and families can come and change seeds. The seed bank and library offers an alternative model to agricultural biotechnology through participatory preservation of organic seeds.

THE PROPOSALS AND THEIR RELATION

This is how the project is conceived in its context and how it could have had developed over time:

By the big pond Behlvar Dighi an idea starts to develop: how to turn the water of the pond into drinking water. The huge body of water is used for washing, cleaning, bathing but the water is not clean enough to drink directly. It is tempting though, especially during the hot summer months, when there is a shortage of water and the supply from the city municipality is unpredictable. Moreover, the queuing by their public wells can take hours every day. There is a need to get clean drinking water by finding a technique that is low-tech and self-sufficient.

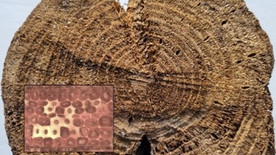

Another condition that characterizes the context, similar to the abundance of water, is the ground, with layers of soil, thick and rich in clay. Through the local knowledge and the culture of brick making techniques, (manifested throughout Bangladesh) the suggestion to burn the clay and turn it into ceramic is not farfetched.

By the big pond the local community starts to refine this material, the clay. They are producing a new element, that of a ceramic filter that cleans water. The basic equipment required for starting up this production is attained through a local NGO. Through international organizations, such as for example “Potters without borders” local NGOs are initiating this type of low-tech factories at many other locations.

The water filter is a good thing, providing families in the neighbourhood with clean water, direct from a source at home and at a very low cost.

But can the filter be modified, used for something else?

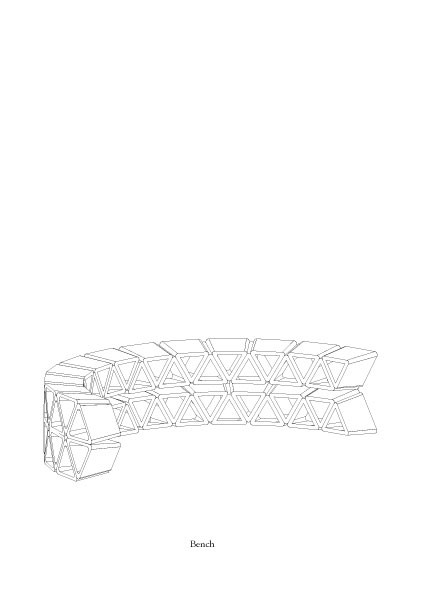

The salon, with its niches for conversation and discussing, of gathering and sharing knowledge, works as an initiator here. A forum through which the single-use of the filter is questioned and can be developed. For example, the filters that are cracked during the production, can they be recycled? And the filters that have been clogged after four years of use, and that no longer are functioning, How to re-use them? A first, intuitive act is to plant flowers and vegetables into them. It is after all a clay pot. Then, by stapling them, small benches are being set up. The pots are casted into walls, for cooling and storage. With the equipment and machines already available, comes, the idea of modifying the actual mould, the press of the filters. Instead of the cylindrical form, the filters now get a three-sided shape, for better resilience and construction ability.

The production starts, along with imagining new uses for this ceramic element.

To replace walls in existing houses becomes popular. When put next to each other the ceramic pots defines the form of the walls and thereby rooms; semi-circular or curved, which gives nice places for sitting and also looking out (if one takes out the bottom of the pot). The same goes with the roof, where the bricks create arches. Here they also serve as an element for natural ventilation, where the hot air between the tin roof and the clay pots creates a natural drag of air.

Parallel, approximately four kilometres away, towards the seashore, farmers and families that are involved in cultivation of rice and crops start to discuss how to cope with rising salinity level in the soil. How can their crops withstand these changes? How can local seeds and crops slowly adapt to the new conditions? The farmers begin to gather by the rice fields and the low walls that separate them. Walls are then being raised and rooms are being built. A small education centre where to learn and test cultivation methods. As time goes by, there emerges a need for storing and archiving local seeds and plants.

By then the production of ceramic elements in the salon is flourishing.

The people involved in the production have once already been in contact with the rice farmers, when they needed rice husk for producing the porous water filter. The farmers that now are planning the seed storage come to think of those filters, how these actually could be quite suitable for their plans. They have already seen some quite inspiring examples, regarding building walls and roofs, over there by the pond. Maybe the modified filter, the ceramic brick, could be used as an element for building up their storage of seeds as well? By stapling the pots, curved walls are formed, with its cavities serving as containers for the different types of seeds. Once the pots find their way in to the garden, in form of the seed storage, the use of them expands. Reinforcement of pond walls, containers for nursing of small seedlings and shrimp fry, planting of crops. When dug down in the earth they serve as irrigation vessels, as well as shaping the landscape, and making it possible to grow things vertically. Other uses for the pots are as tiles that mark the path in the landscape-garden and that stabilize the ground surface, especially during the monsoon.

The soil, the clay and in extension the ceramic element is what on a very elemental level joins the garden and the salon.

They are also joined on a conceptual level by both being sites for production and sharing of knowledge, each with their own architectural articulation. They are rooted in the scale of the community, where participation is a keystone, and the architecture and it artefacts can be adjusted and modified according to the needs and creativity of its users.

This project is not offering a solution or answer to how to deal with problematic questions, regarding for example the right to clean water, women´s empowerment, community building or environmental changes and challenges. But these topics have been influencing the whole process, and are incorporated within the project. Probably there aren’t any straight solutions or answers, and the project work is realizing and embracing that. The issues are taken seriously, and as a point of departure, but emphasize on the importance of imagine and suggest worlds and realities that carry a bit of vision and marvel. To be able to see beyond the most basic necessities of the context.

In cities like Chittagong, where there are no excess of time, money or leisure for most people, and where working days can be long and physically exhausting, it might be precisely the extraordinary and imaginative that the people need.

A suggestive architecture, that take stand from the every-day life, will give precisely this power of realizing through imagining.